I’ve learned over the years that when an opportunity for spiritual inquiry presents itself to me, I take advantage of it only when I feel strong enough inner motivation to do so. In my recent post, “Who Am I Now?”, I wrote that I felt moved to begin examining the question of “self” after noticing the discomfort I felt as my various “selves” began slipping away during this pandemic. But that unpleasant feeling is not all that’s made me so committed to this practice now.

You may recall, from my earlier posts, that I experienced a series of panic attacks at the end of 2019. Whenever they came on, the fear that I was dying rushed in and overwhelmed me. That in itself isn’t surprising, but what is odd, is that this was the second time in a few months that I’d had to face this fear: Back in the late summer and early fall, a super scary situation developed that involved someone I barely knew. I spent the five or six weeks it took for things to reach a (peaceful) resolution, in a state of terror and anxiety that I might be physically attacked. This was a really tough time for me.

During both of these experiences, I turned to my spiritual practice with great intensity. What ended up helping me most was keeping my focus on the present moment. Every time my mind began spinning off into scenarios of all the horrible things that might happen in the next minute or hour or days, I reined it back in and turned my attention to what was going on right then. “In this moment, you are safe.” That was my mantra. This practice didn’t prevent the fear of dying from arising, but it gave me a way to cope when it did pop up. I was so thankful for that!

I was also genuinely grateful for the chance to deepen my spiritual practice. There was even a moment after the panic attacks had faded away, when I thought, “Now that things have calmed down, will you still be motivated to keep practicing present moment awareness?” I wasn’t sure I would be. Then something else occurred to me: I realized that although I’d gotten through these hard things, but there would always be a next hard thing. That’s because – just like the fabulous occurrences and the calm patches – hard things are regular features of life, not anomalies. Given that fact, then, I concluded that I needed to find a reliable way to move through them with ease, instead of freaking out each time they came around.

Looking back, I guess I was really asking for it right then. I think my inner self interpreted my musings as an official request for another life-or-death challenge that would force/allow me to practice getting through the inevitable hard parts of life. My inner self found a very effective way to grant my request. “Here you go.” (Picture it smiling, holding out a beautifully-wrapped package, with fancy gold ribbon.) “Have some COVID-19 symptoms.”

I received this gift in the middle of March, when I’d begun self-isolating, and was feeling very fearful and anxious about the virus. My fear intensified when, a few days into isolation, I got sick. Had this been any other winter, I would have thought, “Okay, something’s working its way out of your body. Just take it easy, and you’ll be fine.” But now, since I had been reading the news reports obsessively, I was well aware of the way COVID-19 symptoms usually progress. I still retain the clear memory of the panic that overcame me when I developed a fever, on the heels of a sore throat and dry cough. Although I managed to stop my mind from endlessly reviewing the details from the news, the anxiety remained. At its foundation lay the same terror I’d experienced in the fall, and then again in December: I might just die. My body might not survive this, and then I will be dead. This fear persisted, even though the doctor saw no need for me to come into the clinic: I wasn’t short of breath, and my fever wasn’t very high. I had no desire to crowd into a clinic waiting room, so I was happy to stay put. But that meant that I was left to my own devices at home, where scary thoughts were continually trying to get my attention.

During this period, when my symptoms persisted, while the fever hung on, I latched onto every single tool in my spiritual tool box. The present moment awareness practice, in particular, was a great help. “In this moment, you are okay.” I repeated that a lot, although I did eventually change it to, “In this moment, you are alive.” Even as I repeated this sentence in my mind, it felt overly-dramatic to me. But I couldn’t bring myself to go back to, “You are okay”, because how could I feel like I was okay with all these symptoms?? Once it seemed like I really was, by all objective indications, on the downslope of the infection, a twinge of fear – or sometimes panic, even – still rushed through me every time a little chill came on, or whenever I felt a scratchy tickle in my throat.

It was after one of these moments of terror had arisen and faded away, that I thought, “This is just horrible. I can’t live like this.” What I meant was that I didn’t see how I could possibly make it through life if I was going to be overwhelmed by panic every time my throat started to hurt. At this point, I was mostly recovered from whatever I’d had, but still felt very tired. So, I had a lot of time to sit or lie around and think. That was when I cast my mind back to the two other experiences of terror I’d gone through in the previous six months. Just as I did when I found the dead sparrow on my porch recently, I began looking for a message. It seemed to me that these three experiences must be linked by some common thread. If I could find that thread, I reasoned, it might help me find a way to make my way through whatever hard situations life throws at me.

As I was tucked cozily under a blanket on the couch one day, with a purring cat to keep me company, In Love with the World suddenly came to mind. I remembered how much it had helped me before to read Mingyur Rinpoche’s account of how he had gotten through the difficulties he encountered on his retreat. So, the next day, I opened the book back up and started reading it again.

What Rinpoche wrote about the “self” and impermanence had spoken to me so powerfully the first time I read it. Now, returning to these opening pages, I recognized that in all three of my difficult experiences, the thought of my body dying had thrown me into a panic. Because I was identifying my body as my “self”, the thought of losing it terrified me. I was clinging to the idea that if my body failed and died, then that would be the end of my “self”. So, in all three of these recent situations, I had desperately sought to protect my “self” by protecting my body. And it was my strong belief that I needed to protect my “self” from dissolution that caused me all the mental and emotional suffering.

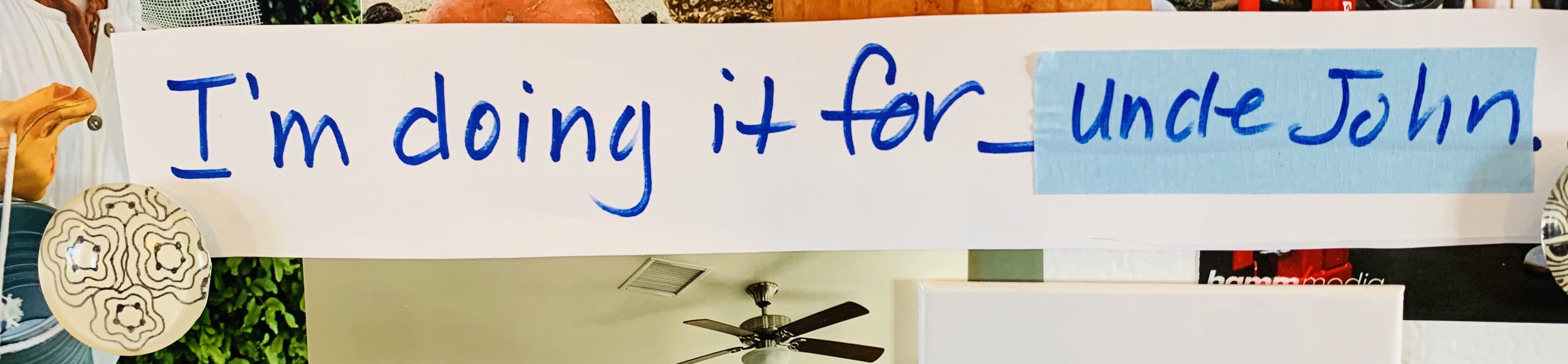

The next morning, during meditation, I considered this question: How would it feel to be going through this pandemic if I fully knew that I am not my body, that there is no fixed “self” the virus can threaten, no “me” the virus can kill? As I reflected on this, I noticed myself begin to relax. It felt liberating simply to contemplate the possibility of being able to move through life in a state where I wouldn’t see every ache or pain in my body as a threat to the existence of my “self”. Just the idea of mentally letting go of clinging to my body as “me” was comforting, calming. And I’ll take even that slight comfort any day, over the suffering I’ve felt keenly since last fall. But there’s another way I’ve benefited from this reflecting on being sick during this pandemic, too: Realizing how my view of my “self” causes me to suffer has really ramped up my motivation to explore that “self” and to practice letting go of trying to protect it all the time.

Thanks for the opportunity, inner self. Really, I mean it.

May all beings be free of suffering and the causes of suffering.